Tirana is so clean because nobody has anything to throw out – Anonymous

Albania was never intended in the original travel plan. I don’t know anything about this country other than the fact that I like and eat burek almost every day now. Burek or borek is a kind of baked pie you eat for breakfast, lunch, dinner and snack or whenever your stomach comes calling. It is made from thin, crispy dough stuffed with either minced meat, potato, cheese or spinach. It is bigger and fulfilling than a slice of pizza, and more important it costs only 1 or 2 euro which explains why I eat it every day. Uh, and what does burek has to do with Albania? Maybe it doesn’t because I don’t remember eating and even seeing one burek in Albania except that a Croatian told me that some time ago, Albanians brought this delicious pie over to the Yugoslavia.

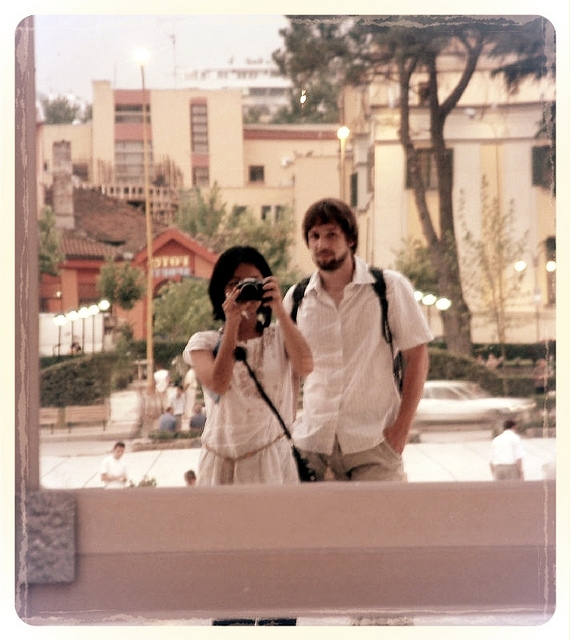

Jarda and I wanted an easy vacation at a few touristy spots in Croatia, Montenegro, lounging by the beaches and sweating over nothing. That fateful day on the street of Budvar, a beautiful city on the Montenegrin coast, I saw a bus tour promotion to Tirana, the capital of Albania, and all of the sudden, my curiosity got the better of the hedonistic pack I made with Jarda before the trip: doing boat trip, eating a lot of seafood and seeing beautiful things. I turned to Jarda and suggested, more precisely announced our next travel destination. The forever over-planned Jarda quickly dismissed the whimsical idea and presented a briefcase full of arguments why we should not. “We are not prepared. I don’t have any guide book. Why didn’t you say that before?” The street conversation quickly distorted from a sensible discussion between two rational adults to a true-to-style Balkan explosion. “You want to take me to a dangerous place. What if something happens to me?” What the heck can happen to him? “Dangerous place? My ass. Only the fool who has never been to this region make up to justify not moving their asses anywhere.” No offend to you really, I wanted to make a good case.

But to be fair to Jarda, a few days ago, prior to the vacation, a Bosnian colleague, Arnida, warned me about the “barbaric Albanians who hate Serbs, so they hate Bosnians because we speak similar languages. They don’t care if we are also Muslims. They were isolated during communism and knew nothing.” She brought up our recent school trip which we traveled by bus to Greece from Sarajevo. Instead of going through Albania, the route was diverted to Macedonia. Another Bosnian, my roommate Tena, roared into uncontrollable laughter when I sang the word Albania to her as if going there was something unthinkable. What is wrong and funny about this country? I pondered for a few more days before completely forget about it until now. My local friends’ discouraging attitude and Jarda’s dismissal have clearly affected me and made me worried about this country I know next to nothing. To show how seriously I consider their concern, I do think about how I would put Jarda’s life in danger when we finally meet these ‘crazy’ Albanians. But I don’t want to accept the kind of misinformed bias which we often commit about places we’ve never heard of and people we’ve never met. I become more and more convinced and refuse to drop this ‘Albanian adventure’ subject. And there I am on the side street of Budvar, I dig deeper and deeper into my soul and remember a technique successfully proven since ancient time.

I started to cry.

(Because it works. That’s why.)

“Hic hic. I don’t need roses, lilies or tulips. Hic hic. I don’t want jewels, diamonds or jades.” I closely monitor the reaction from the object of my affection while I speak, “I want only Albania. Hic hic hic!”

And it worked.

Jarda agrees on a condition that we will seek more advice from our Montenegrin-Serb owner at our accommodation before reaching the final conclusion. “Yeah. No problem. Go! Tirana is a nice place.” The owner assures to my relief. If a Serb does not mind Albanians, why should two foreigners have anything to worry? And from this day onward, we spend every evening visiting Internet shops to search for information on how to get to Albania on our own. The simplest solution is to buy a tour package from a travel agency, fill our backpacks with bureks and enjoy our easy bus ride to Tirana. However, this is an insult to a budget backpacker who prides on his resourcefulness at finding a workaround with a minimum cost. Armed with transportation advice from virtualtourist.com, we hop on and off many furgons or combi minivans privately operated by individual Montenegrins as an alternative mean for public transit run by the government or long-distance buses run by large enterprises. There isn’t a direct route between Budvar and Tirana using these furgons; we rely on the Montegrins to tell us where to go to catch the next one going to city X to connect to city Y to eventually reach Ulcinj, the border city of Albania. In Ulcinj, we are directed to a minibus destined for Shkoder, a city in northern Albania, where we are told that we can take another van going to the capital. By then, Jarda and I have gotten used to this kind of unusual transportation, and we both enjoy it a lot. But things in Montenegro are more civilized. The Montenegrins are more similar to the friendly Bosnians and Croatians whom I’ve met, and we are able to stumble our way around using my limited Serbo-Croatian, and we don’t feel completely lost.

Albania is a different kind of world. Jarda is surrounded by scrutinized locals who are not used to seeing tourists with this sort of transportation. At first, I was a bit afraid, and my mind being fixated on the warning from Arnida. What choice do I have now? I am on my way to Albania and sitting next to a full load of Albanians, why don’t I just enjoy the journey. I loosen my grip on the camera I hide in my shoulder bag. Seriously if they decide to rob me, I can’t possibly resist against a full van. I begin to look at people…discreetly. There is a junior wannabe pimp sitting in front of me, dressed neatly and covered in flashy accessories. As he is the only one who can speak English, we warm up to him in case we might need a local junior godfather if we will find ourselves in trouble. The teenager proudly advertises the abundance of his country. “Whatever you want, you can buy here.” Even a brand-new Mercedes for a portion of the price, I should add. One day you return to the car park and see an empty space where your Mercedes used to be, what do you do? A) Report to the police? B) Post a classified add begging the thief to return the car? (this actually worked for a lady who sent the thief messages and emails and he felt so sorry for her and eventually returned her belonging.) C) Visit Albania and get your car back or buy a new one at a lower price? The teenage future local boss enthusiastically tells us about the time when he was a boy, and Albania was isolated from the rest of Europe. A relative gave him a Coke, and after finishing the drink, he kept the can to show off to the other kids.

If you lived in communist countries, you would understand the desire for all things made from the west, especially those MADE-IN-USA and the pride for any association with anything Western, even an empty Coke can which usually finds its way to the dumpster. MADE-IN-USA are priceless because they are forbidden fruits. They provoke this desire to be cool, the urge to acquire. The more they are forbidden, the stronger the urge and desire. To those deprived neighborhood kids, the Coca-cola was not just any can; it was a can of Coke, the symbol of America which in turn the quintessential symbol of the west. The father of a Croatian friend of mine, Ivan, once went on a trip to Russia during communism, and there he sold the made-in-USA jeans he was wearing to a Russian. The money earned from the sale of one pair of old jeans was enough to cover his entire trip. In a way, I can totally understand. When I was a kid growing up in Vietnam, my grandfather, who lived in America, sometimes sent gifts home. My extended family (rather large) had a countdown to the day we could go to the post office to pick up the package. My parents would let me skip school to participate in this important event. You hear it right. It wasn’t a normal delivery; it was an event. The pickup often took at least half a day in a large, hot room packed with hundreds of people who were also waiting to pick the material love from their relatives from America. The room was like a heated indoor zoo where sweaty people shouting to one another. By the time we got home, I was dead tired from the waiting, the heat, and the ride home during a hot summer afternoon, but like the rest of the family, I was filled with happiness and pride, packaged and delivered in a box from America.

I remember vaguely the anxiety and joy with every rhythmic bouncing up and down on my butt during the bumpy ride from Ulcinj to the Albanian border and then to Shkoder. The reckless driver drives as if he is gunning for Formula 1’s 1st prize on an extremely narrow country road. One minute, I am anxious and bothered by the thought of being robbed or kidnapped by a group of skinny Albanians jumping out from the bushes. The other minute I am overjoyed by the unusual experience. When we arrive at the border, the driver collects our passports and 10 dollars each to hand them to the customs police to pay for the entrance into the country, not bribe as I initially thought. He drove us to a street and dropped us off telling us to wait for another furgon to Tirana. An hour later, our driver arrives. He is one tough looking dude with razor sharp eyes and hairs hanging over his shoulders. Without saying anything, he signaled us to jump in. I get a bit anxious again. Whoa! Slow down! Similar the driver before him, and wait for the one next to him and another one behind him, our driver drives like a mad man. He passes one car after another on a highway with only two lanes. From time to time, our car is sandwiched between two others flanking on the side, either the right car tries to pass us on the right or we try to pass them on the left. Three cars on parallel on two-way lanes. Jarda and I duck ourselves in the car like two active participants in a car racing video game and hold onto the seat for dear life whenever the driver perform this passing ritual. A couple of suspending hours and we miraculously arrive safely in Tirana without any visible physical injuries, but not sure about long term damage to our nerve.

Furgons are not allowed in the city center. Good law. These furgon drivers sooner or later will run down all the good citizens of Albania. We walk from the furgon ‘station’ to find our way to the center. The place where they call ‘station’ is, in reality, a muddy and dirty vacant lot next to some building under construction. The whole city seems like to be under construction. Oh, my god! Is this still Europe? I feel as though I am standing on a street of Saigon. People are riding left and right on old bicycles. Old men hold stacks of LEKE (Albanian money) and EUR to do their money exchange business on the street. Other decently looking old men, with shirts neatly tucked in pants, obviously have nothing to do on a weekday, are lying right there in the park either sleeping or just enjoying the view. Oh, my god!

Having triumphantly survived on Albanian highway, now we are pondering about our next crisis, money. No one wants to accept my Master credit card. I didn’t bring my debit card for fear it would be stolen, and money from bank account would mysteriously travel thousands of miles across the Atlantic to the Balkan. Jarda brought no card because he relied on me. We have almost used up our cash after we paid by cash for almost everything on this trip. It’s entirely our fault, no one to blame. We travel to these less developed countries and expect the locals to happily cater to our very need by swiping our credit cards and bring back the receipt and a pen to sign on a silver plate. I put 20 euros in my sock in case we were robbed; we are still able to buy tickets to run away back to home. We enter a Western Union to discuss whether I should call home to my mommy or Jarda’s friend in the US to wire us some money so we can continue with our trip to visit Kosovo. I am not fond of the idea of asking money from people to do something many consider as useless as traveling, and also I have to tell my mom where to wire me the money. Albania. Are you kidding? Tired by thinking and discouraged from the sight of the city, which there isn’t any, plus being clueless about what to do and where to go, we decide to stick to our original plan and go home in a few more days.

The money issue and the uncertainty don’t stress me out as much as Jarda’s constant complaint that I didn’t prepare, that he doesn’t want to be a homeless implying we might be sleeping on the street if we don’t find any accommodation, that if we don’t find a cheap hotel, he will pay hundreds of dollars for an expensive hotel and blah blah blah. I am completely stressed and annoyed to the point I want to secretly make a pack with an Albanian furgon driver and send him back home on his own. He is out-of-whack on his first trip to an ‘uncivilized’ country, and instead of realizing that it is completely normal, the common discomfort of a first-timer, he thinks I am Akon and puts the blame on me, but unlike the rapper, I’m not accepting any. For a while, I think that we might as well check in a regular hotel and enjoy a first-class traveling experience, but after half an hour walking and asking in ‘sign’ language, we found a budget hotel for 25 dollars per night. Not bad really for coming unprepared. The no-frill hotel is located in a decent area, well-decorated and the room looks very reasonable. Tiny but who cares? Phew! I feel like a huge weight has been lifted off from my back. Jarda didn’t suffer from a car accident. He didn’t become a homeless person. And he didn’t make me spend the last chunk of money that we have. We are quite alright.

Without a guide, we set out to walk the street and watch the lovely people while being watched by them. In the end, there is a lot of watching. The streets are full of old, rusty something. I say something because they are some objects, not even cars. They are moving because of the engine alright because I hear noises, but there are some metals, leftover from cars mixed with spare parts from other running machine. On the other hand, expensive cars like Mercedes flood the street. I was told that they are smuggled here after being stolen in other countries in Europe. Kids follow us in rove to beg for money. When I pull Jarda away, one girl, before walking away, pinched me on the inside of my upper arm where it really hurts. Seriously, this isn’t Europe; this is like Vietnam. We walk past the American embassy and are surprised by the number of guards. There must be a dozen of them, all dressed in black and holding guns ready for action.

Not having enough money for Kosovo, but we can go to some other city if we closely monitor our spending. We check our budget and agree to visit the coastal city Vlora in the morning. There is no reason apparently. We pick the name out of convenience because its name is printed in the bigger font on the map, therefore a major city with easy access and available accommodation.

Enver Hoxha, the communist dictator who became premier in 1944 after Germany withdrew from the country, closed its door to the rest of Europe including the communist neighbors. Hoxha was closed to Tito’s Yugoslavia in the beginning since the mighty next-door neighbor helped establish the Communist Party. After Tito ended the honeymoon with Stalin in 1948, so did the tie between Albania and Yugoslavia. During the years after Stalin’s death, the new communist leader Khrushchev started the process of De-Stalinization by removing Stalin names, statues to lessen communist giant’s influence. Hoxha felt that the Soviet Union had thus gotten too liberal and cut the tie in 1961 when Russia began to renew the connection with Yugoslavia. Albania removed itself from the Warsaw Pact in 1968 followed by Russia’s invasion of Czechoslovakia. (Czechs should consider Albanians their new best friends after having betrayed by both the Western and Eastern allies.) Not looking up to Russian Stalin, Hoxha turned to China’s Mao for both economic and ideology support. By then, Albania was the only Eastern European ally of China. But China-USA rapprochement in the 70s led to Hoxha severing tie with the Asian ally in 1978, the last tie, and closed the iron gate shielding Albania from the rest of the world until his death in 1985. Albania didn’t open until 1991 during the snowball effect from communism collapsing all around eastern Europe.

Communists are by nature suspicious and paranoid. Isolated communists are even more so. While other countries built schools, bridges, and houses, in this tiny country with only 3 million people, 700,000 bunkers grew out like mushrooms from everywhere. Albania was the first country to declare an atheist state. These bunkers were built both to protect the country from outside attack and to project the illusion of constant fear. The brutal dictator has long gone. Communism ended more than two decades ago, and the Albanians are eager to change and step into modern Europe. But with the ubiquitous presence of the bunkers, it’s hard for anyone to forget and for outsiders to take them seriously.

Why then, you may ask, can’t Albanians just bulldoze them down like we knock out buildings? Well, I will tell you a story. Sometime in 1950, an excited-to-please chief engineer of the bunker project submitted the prototype to the communist government. “How strong is the bunker, comrade engineer?” asked the communist boss. “Very strong, comrade party leader,” replied the engineer. “Even with full assaults by tanks?” “Definitely, comrade party leader.” “Good. Now, please step inside the bunker, comrade engineer.” The obedient, unknowing engineer stepped inside the bunker. Few minutes of under firing from combat tank, the dizzying engineer walked out to receive a good new of his life, that his prototype has passed with flying color.

What is the morality of the story? The answer is that the communists should not have fired at the bunker with a living person in it. And you believe that? The point I am trying to make is that the bunker sustained attack from a real tank, do you think a bulldozer will pull it off as it easily does your full-duplex? Oh yeah, and there were about 700,000 of these babies.

In the 70s, probably followed the news of Russia’s invasion of Czechoslovakia, more and more bunkers were added to become part of Albania’s infrastructure. These bunkers are varied from sizes. Some are small enough to hold a soldier with his gun while the others can be as large as to house an entire family. There are four different kinds of bunkers: military strategic, big towns, coast and countryside. Most of those I see are coastal bunkers during my ride to Vlora.

Nodding head means no and shaking the head means yes in Albania, creating a few hassle when we communicate with the locals. When drivers flag us on the street asking if they can drive us somewhere, we turn them down by shaking our head, but they use their non-verbal language to interpret it as a yes and open the doors for us. I switch to their language and nod my head, but they use their universal code and interpret again as a yes and nod their heads back at us saying “yes yes?”. I shake my head again, and I lose track of the movement of my head. I don’t know a single word in Albanian, and no Albanian speaks English, so I rely on my ability to hand gesture when I need information. Bargaining about prices is easier since I can just write the numbers on a piece of paper or show my fingers. Sometimes I turn to Jarda and ask if he wants to ask for direction and bargain with the locals, but being a ‘civilized’ person that he is, he just smiles gently at me. Anyway, we find the driver who drives to Vlora.

Someone on an Internet travel forum recommended people to make a road trip along the coast which he describes very beautiful, and not knowing any other better alternative, I happily abide. I am very anxious to see the coast, but all I see are dirty streets, highways, and of course bunkers protruding out like mushrooms. In rare occasions when the highway caresses the coast, I can spot a vague blue streak of the ocean from far away. At the same time, I am distracted by a boy selling fresh fish, sitting on the side of the road and aim the camera to take pictures of him. By the time I finish my mission to show the face of the fish boy on the front page of The National Geographic, the sea has disappeared again. Our driver occasionally stops during the ride, not only to pick up additional passengers but to run various errands. Once he stops to buy a couple of watermelons. I’ll be happier if he stops more often to buy fish, pants or whatever Albanians bring to the highway road to sell.

The driver is kind enough to drop us off near the sea instead of abandoning us on the street. We pay and carry our heavy knapsack and walk toward the beach singing a happy tune. The closer we get to the beach, the sadness is shown clearly on our faces and wonder if what we see in front of our eyes is a reality. Reality bites.

Good Jesus! In front of us is not a white beach with clear blue water with fat fish jumping up and down. There is nobody bathing under the Adriatic sun. There is no salty smell of the sea. Instead, we are walking to a garbage dump where the locals litter trash.

I frantically try to do some damage control, brainstorming with Jarda on how we are going to get to the real coast, how far it is from here, should we camp out somewhere. It is possible to walk to the beach with it being 6 km away; any real backpacker could have done this easily. But we are two dummies with no map and no guide, and it is already 5 o’clock. It will get dark by the time we get there given that we find the way. I have a confession to make; I am afraid of the dark and the spirits and the holy ghosts wandering in it. Seriously.

Having no choice, we walk back to the city center looking for a hotel. The Albanians, being typical friendly in-your-face style, gather around us to help. A group of five ask and repeat the same word I spell out to them “hotel, hotel?” and pointed ‘there’ to a decorated hotel we have checked earlier. I shake my head and rub my thumb to the tips of my other fingers to tell them that we don’t have that kind of money. Then these men shout across their neighborhood for more people to come and help. These men and women are covered with glittering gold jewelry remind me of the Vietnamese in Vietnam. I haven’t seen any European wearing this much gold. In a poor and developing society, people tend to pay more attention to ‘signal’ products to signal their significance and wealthy to the outsiders. These people keep asking me ‘Italiano’ to see if I can speak Italian with them. Of course, I can but let it be warned that my Italian is something like this “Si, yo hablo Italiano, senor!” And I string a short sentence with half-broken Spanish, English, and pathetic Bosnian in addition to the confusing shaking and nodding of my head; I come up empty in my search for a budget hotel.

We thank the friendly locals and left to find the hotel ourselves. We don’t get very far from where we first met the group of helping people when we find a square and sit down to rest, to look around and about, at buildings, at the messy streets, at the strange people and at this kid with a sad face who is walking with his bicycle around the square before sitting like me, in front of me. We sit there for a long time on the steps thinking where to find a budget hotel until we see a clean looking couple pushing their baby. The husband gives us some tip for a hotel, and five minutes later, we got what we wanted: a dirt cheap hotel. What we didn’t expect was that our hotel would be something like a place they put immigrants who came from poorer countries to work on construction sites. Albania is already the poorest country in Europe, so you do the imagination. Electricity sockets fall off from holes on the wall. The room is painted green and isn’t bright so I can not really tell the color was chosen for an aesthetic reason or for covering up mold. Oh but the room is still ‘EU’ standard compared to the bathroom. I should not call it a bathroom because then it has to follow a certain rule for a room. It is a mixed between a factory and storage where there are a collection of faucets, metal pipe hook on the walk and plastic buckets to hold water. I carry my clothes into the shower factory, looking at it, walk out, carrying my clothes back again, walk out. This is one hot summer. I was and will be in contact with many civilians. I have to bathe. I enter the shower for the last time, close my eyes pretending I am hearing a fat lady singing opera outside the window “Oh Mio Babino Caro” and imagining heaven. And it was the shortest time I’ve ever been in heaven.

Hungry and tired after the return drive back to Tirana, we ask around for a restaurant. By that I mean we coherently shout out only one word ‘restaurant’ while coordinating our hands and mouths indicating the act of eating. The overly helpful bystanders show us a shack near the bus stop, and we dutifully walk in amidst the staring eyes of the locals who don’t often see tourists in this part of Europe. The waitress brings a menu as part of their daily auto pilot tasking knowing fully well we understand Albania on the same level she understands Yemen. I don’t think there is such thing as Yemen language, but you know what I mean. I point to a man who is slurping on a meat stew dish at the next table. The waitress immediately understands my order and proceeds to the kitchen. It must have been the sun and the stew that cloud my travel judgment for I have violated one of my travel rules: never ever order something from a country such as this before knowing the price unless you don’t mind to pay double than the normal price. But I worry too much after all Albanian are still European, they must have some pride not to cheat tourists over some trivial thing such as beef stew. The cook/waitress write down on a piece of paper the price, and to our delight, it is cheap even if she might have cheated a little. We shake our heads, and she goes to the kitchen to prepare our meals. Shake our head and the lady obliges? Have you forgotten that Albanians shake head for yes and nod for no? There is meat, broth, some vegetable in the stew, and it is entirely edible; I don’t expect much anyway from a shack by the bus station.

After leaving the restaurant, we are thrown back into this pandemonium life outside where cars are honking nonstop and strange people standing everywhere. We try to locate a bank to change the money back into EUR and see a minivan with a sign to Kosovo. The one-way fare costs only $35, but I regrettably tell him that we are going home today. I have never felt this disappointed during my travel before. You can not come so close and cheap to Kosovo where I am now. But we are running out of money, enough to pay for transportation back to Montenegro and a bus ticket to Sarajevo. Neither of us brought a debit card, and no business accepts the credit cards we brought. We didn’t do enough research about the country. We don’t know where we sleep nor where to go. This kind of spontaneous traveling is perfectly fine if you are not short on cash where people only accept cash. But the real reason is I am afraid, and so is Jarda who was even afraid by Albania before our arrival. Kosovo has been trying to leave Serbia, resulting in numerous fights beside the full-scale war in the late 90s. Any mention about Kosovo connects to violence and wars, so who wouldn’t be afraid coming unprepared.

It is difficult, but we eventually walk away from this Kosovo bus, ready to go home. Then I see the same long-haired driver who drove us here. I shout from across the street, smile and wave at him as if I have just met my long lost friend. It isn’t an overstatement; when you are in a strange place, the person you meet only once can provide you a sense of familiarity and secure that you secretly crave after. The driver recognizes us, running from across the street with a big smile on his face asking if we are returning to Skhoder. At that moment, he looks like my guardian angle instead of a mean-looking predatory just a few days ago. Is perception a funny thing?

With every Albanian driver seems to be busy, I see more episodes of three sometimes four cars side by side, trying to pass another. It has to be my paranoid and imagination otherwise I have to swear we almost had at least one car crash. But it finally dawns on me that this is the way the Albanian drive every single day, especially those who drive people for a living. This has become their sport which they manage to master wonderfully albeit not for the fainted heart. A few other “Oh my God!” and we arrive safe and sound in Tirana.

If you are expecting a nice vacation and not a cultural adventure, please do yourself a favor and look elsewhere since you will not enjoy a single minute while regretting money not well-spent.

Western backpackers travel to this country to get a feel of closed society from the past. I don’t think there are many closed countries existing anymore. The world we live in now has become more and more connected as we become more opened societies. It is no longer a problem to break down the wall and enter a closed society. Instead, the problem lies on the close-mindedness from opened societies.

6/2006

[slickr-flickr type=”galeria” tag=”albania” caption=”on” description =”on”]